We speak with Dr Craig smith about his research on whale fall ecology, and how these animals sustain life after death.

Listen to the full interview on The Deep-Sea Podcast

want to be notified when new interviews are released?

Dr Craig smith

Professor Emeritus of Oceanography at the University of Hawai’i.

So Craig, let's start at the start…

what is the journey from the surface to the deep sea, that begins at the point of death of a whale?

Well, most whales - contrary to popular belief - sink when they die. Many whales are migratory species and so they live in one part of the ocean (often at high latitudes) and migrate to low latitudes to spawn and then migrate back to their feeding grounds. During these migrations, there is significant mortality and most of the whales that die in the ocean, end up sinking to the sea floor.

They may start sinking slowly, but then as the gas in their body compresses, they sink to the sea floor relatively rapidly, so there's very little scavenging on the way down. As such, most whales hit the bottom of the sea floor intact.

Now, most of the deep sea floor is a very food-poor environment, because most of the food that is available, is very small particles of phytoplankton, detritus or carcasses of zooplankton that sink down to the bottom. The smaller particles sink more slowly and get consumed on the way down, so by the time you get to the deep sea there's very little food availability. A whale fall, in contrast, is a huge gigantic bonanza of food when it hits the sea floor.

so how did we discover this sort of deep sea phenomena?

We were diving with Alvin and we kind of went off-course. I was not in the submarine, I was the chief scientist of the cruise, and two graduate students were running the dive for me and they happened on this huge skeleton of a blue whale, approx. 21 meters long! They were really excited but they didn't use the underwater telephone to call us up and tell us, they just grabbed a random bone and came up to the surface. This happened to be the last dive of the cruise, of course. They took some images of the bottom that weren't very high resolution, but we could see some clam shells around it and a bone, which was pretty cool. But, well, we couldn’t even write a paper on it, because we couldn't see what kind of animals were on it, so that was quite interesting and very frustrating.

So for a year, we didn't have any real data that we could write a paper about, so we ended up convincing the National Science Foundation to give us a grant to go back the next year and do some sampling. Then that was the first whale fall paper in 1989, in Nature.

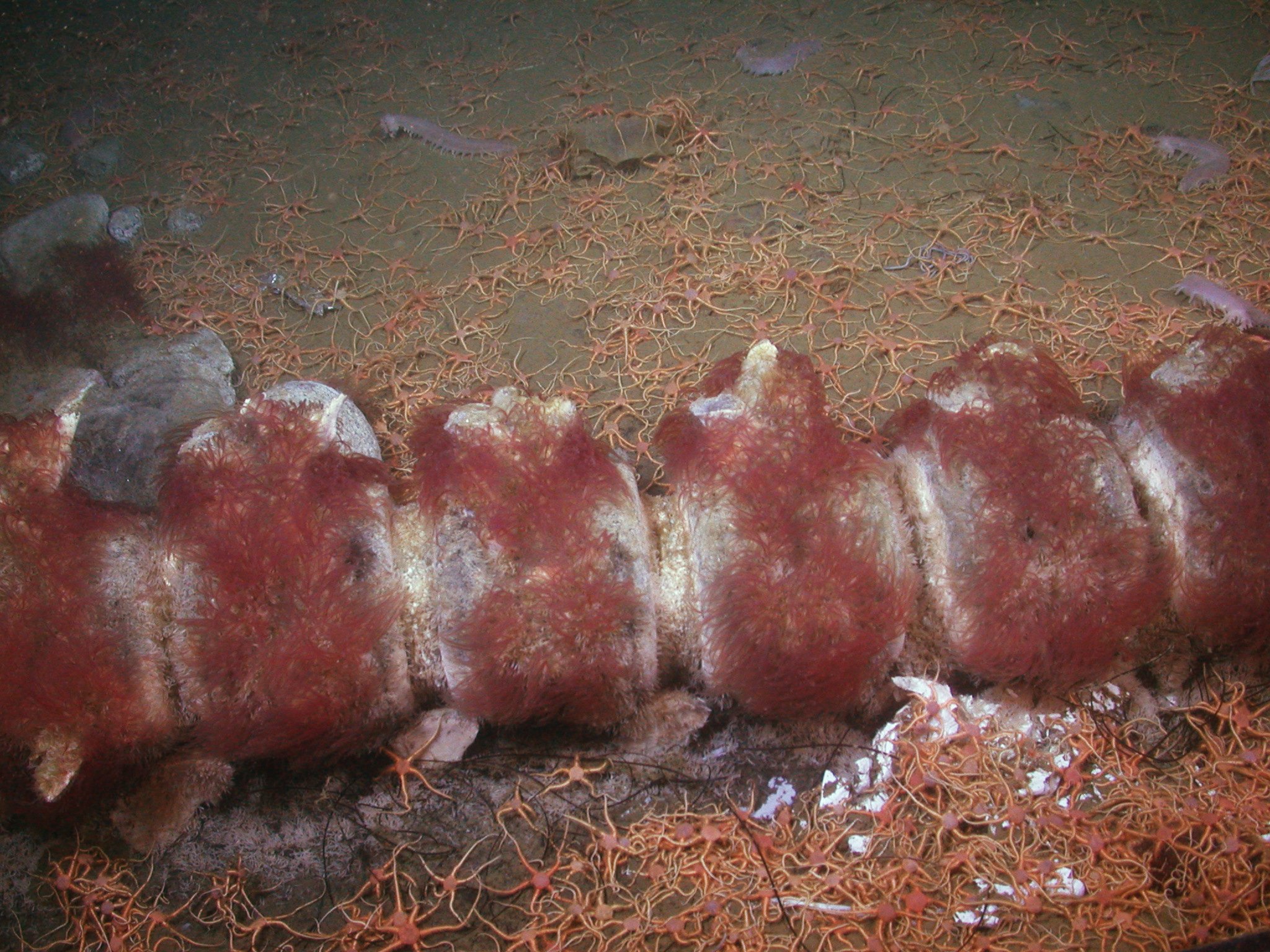

Image courtesy of NOAA

could you talk us through the different stages of the whale fall communities?

Sure! Well, a typical grey whale might be 40 tonnes in weight and a lot of that weight is in the blubber, proteins and also in the oily bones. Something like 10% of the oil in a whale's carcass is actually inside the bones! So when it sinks to the sea floor, the whale may cover 50 square meters at the bottom. In one instant, that’s the equivalent amount of food from small particles over a time scale of 100 to up to 2000 years, depending on where you are in the deep sea.

The first stage is what we call the mobile scavenger stage. This is where large mobile scavengers like sleeper sharks, hagfish, crabs and amphipods come in and ferociously feed on the soft tissue. You just see bits of whale flying all over in the water column around the whale. It’s just a huge feeding frenzy that may go on for months or even years, depending on how large the carcass is and where it is in the ocean.

“It’s just a huge feeding frenzy that may go on for months or even years...”

so, how do these whale falls attract scavengers?

There's some evidence from scavenger studies that they may use sound waves or waves that propagate through the sediment (called stoneley waves), to detect the presence of a big carcass or a big food fall. Clearly, there will be an odour plume. One of the interesting things to speculate about, is what are the compounds in that plume that may be attracting them? During the decomposition of carcasses, there are some compounds that have interesting names like cadaverine and putresine. These are products of microbial degradation and they are apparently used by scavengers in terrestrial environments, like vultures, to detect the odour. So, they may play a role in in the deep ocean as well…we don't know.

so there's the second stage when all of the bulk of the meat is gone and you have a skeleton?

That's right, when it's been skeletonised, we call this an enrichment opportunist stage. That’s because the local sediments and the the bones themselves, are still very rich in organic matter. The local sediments have been organically enriched from some of the blubber being pushed into the sediment when the whale hit the bottom, and also from bits of the whale raining out and covering the surrounding sediments to a few meters.

We called it the enrichment opportunity stage because of the characteristic species, like polychaete worms that use organic enrichment at the sea floor for feeding and completing their life cycles. What's also interesting, is that the community looks similar to the kinds of communities that occur around sewage outfalls in shallow water.

Then stage three is a sulphur-loving stage (and all these stages overlap). During the organic enrichment stage, some of the sediments are so organic-rich that the aerobic bacteria can't break down some of this soft tissue, and the enrichment opportunists don't remove it all, so the system goes anoxic. There's not enough oxygen for the bacteria to use it and break down the organic matter.

During the sulphur-loving stage, we see animals that are closely related, or even some of the same species that occur at hydrothermal vents. We have tube worms and these big white clams that can be 10 to 15 centimetres long that have bacteria in their gills. This stage actually has over a hundred species of animals associated. And in fact, on one whale carcass, we found 200 different species of animals living during this sulphophilic stage.

Finally, there's a reef stage. Eventually, the lipid in the bones does get depleted by bacteria, and then it's just like a rock. The whale skeleton is a a reef and you have animals living on the whale bones as a hard substrate, not using anything characteristic of the whale itself.

Image courtesy of MBARI

has anyone ever tried to estimate how many whale Falls there might be? or how many are going down per year?

We've been doing this for years! We published the first ones in 2003 with some very reasonable assumptions. We estimated with the known population sizes of the nine largest whale species in the global ocean - the great whales - and if you assume that the sulphophilic stage can last at least 10 years, we estimated that there are over 600,000 whale skeletons on the bottom of the ocean in the sulphophilic stage, given the current population density. So that's almost an order of magnitude more than there are hydrothermal vents! The mean average distance to the next closest whale skeleton is something in the order of 12 kilometres.

“We estimated that there are over 600,000 whale skeletons on the bottom of the ocean...”

Now, we can't talk about whale Falls without talking about osedax

Well, Osedax are called “bone-eating worms” or “zombie worms” and these are really bizarre animals. They're worms without a gut or an anus and they bore into whale bones. They dissolve the mineral matrix of the bone with acid, and have this root-like structure that grows out into the bone. They have bacteria in these roots which helps them absorb and digest organic matter, like lipids and proteins. The top of it looks like a little red palm tree that sticks out of the bone to take up oxygen. There are now about 35 species that have been identified, although the first one was described in 2003.

So… how do you sink a whale?

I can walk you through the whole process because it is pretty interesting and there are some unique characteristics of doing it in the US, because of our liberal laws. We've now sunk seven whale carcasses in various parts of the ocean and every one is different with unique challenges.

In the US, when you want to sink a whale, there's something called The Marine Mammal Stranding Network and they keep track of all the strandings of whales. We tell them we're looking for a whale in *this* part of the ocean and so when one comes up, they call us and we and then we fly to that site.

This one particular whale had been floating for 10 to 12 days, and it was stuck under a pier. If you've ever been near a dead whale, you'll realise that it is quite a smelly process. Rotting whales stink like nothing else I've ever encountered. They have this very pungent penetrating odour that you can't get out of your clothes if you touch them.

We had brought six thousand pounds of steel ballast and we kept adding that to the whale, tying it onto the tail of the whale, but it wouldn't sink. So the chief engineer of the boat said “well I have an idea” and so he went down and came up with this big rifle and started shooting at it. This is a technique that can only be used in the US, it turns out that probably all the crews on US vessels have their own arsenal of weapons.

Image courtesy of Craig Smith

That didn’t work so I got down in a little inflatable boat with a knife and I was poking holes in the whale trying to get into the lungs to get the get the air out. I was literally up to my armpit in the whale with a knife slicing around, and that was quite gross. All this gas was coming up, but it still wasn't enough.

Eventually we realised that as the weight from the ballast was pulling the tail of the whale down, we were able to sink it by towing it slowly behind the boat.

We had actually had rented wetsuits when we sunk this whale. We did our best to wash them but we had to hand them back. We didn't tell them to smell the wetsuits but they didn't say anything, so maybe some future divers had some interesting experience.

Finally, having a number of decades under your belt, there must be some misconceptions that you've come across with respect to whale falls?

There is this false idea that Osedax completely destroys whale skeletons. We developed a radiometric dating technique so we can actually take a whale bone from the bottom of the ocean, and tell you how long it's been since it died. There's one whale skeleton that we visited over a period of 18 years, and the sulphur loving community on that skeleton didn't look any different after 18 years, than the day we found it.

We’ve found multiple whale skeletons that have evidence of Osedax boring and no living Osedax on them. We've even found whale bones that are covered with a manganese crust that takes thousands of years to deposit, so we know these bones have been on the bottom for thousands of years.