We speak with Lori Johnston about her work researching the microbial ecosystems that are sustained by shipwrecks.

Listen to the full interview on The Deep-Sea Podcast

want to be notified when new interviews are released?

LORI JOHNSTON

Microbial ecologist at Ground Effects Environmental Services Inc.

so today we have Lori Johnston from Canada. she's an expert in the microbial communities found at the degradation of shipwrecks.

so firstly, let's assume we're talking about relatively modern metal ships, and we're often familiar with the stories of ships like Titanic up to the point that it sinks. but can you talk us through what happens after it sinks?

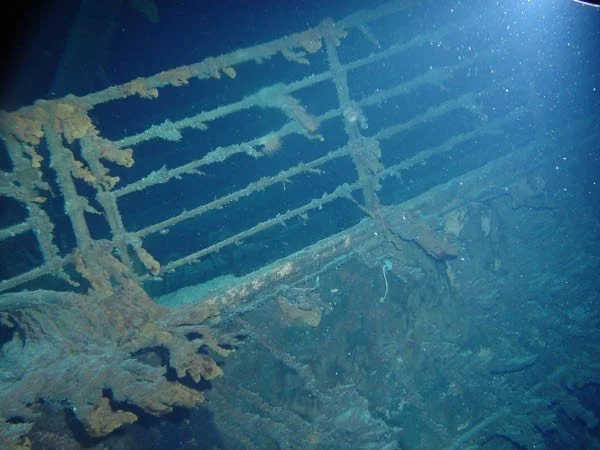

Well, most of the ships that I've looked at are quite deep but after they sink, they immediately become areas for wildlife in the ocean. The flora and fauna of the ocean start taking root and they become quite their own habitat. If you're looking at Titanic, it's quite deep so it takes quite a long time for bacteria (which I look at specifically) to sort of take root and begin to inhabit the shipwreck itself. Obviously, these bacteria are found naturally in the environment so they begin to colonise immediately but we don't see incredible degradation until many years after. 25, 30, 50 years after is when you can visually see the bacteria at work and the outcome of biological degradation of these wrecks.

Is there a noticeable difference between shallow water wrecks and deep water wrecks in terms of how quickly the microbial community start to break it down?

Shipwreck degradation (image courtesy of Droycon Bioconcepts Inc.)

Yes there's a huge difference! If you take, say Britannic, the types of biological growth on that are significantly different than say Titanic or Bismarck. On the shallower wrecks, there is much more competition from biological entities that also feed on bacteria. But those are not necessarily found on the deep wrecks, simply because those biological entities just can't survive at four kilometers below the surface. So, the bacteria on the shallower wrecks are sort of out-competed for resources on those wrecks.

How deep are these wrecks?

The Britannic is not very deep it's maybe 40, 50 meters deep. The Titanic is almost four kilometres and Bismarck is six-ish. It's a very deep wreck and it's a very ominous wreck as well.

So the microbes that are breaking this down, what were they doing before the ship arrived?

The microbes are naturally found in the environment simply because there's elements of iron and sulphur and manganese and magnesium in seawater and in various sediments and rocks. So, they're found throughout the ocean environment itself, but when they're given a shipwreck it's almost like walking up to a buffet because all of these elements are readily available. So, they quickly coat the ship… and I mean obviously these bacteria are also on the ship on the surface because it floats on the water. But when it sinks they have access to just a huge buffet of elements that they need to survive.

so one of the words I learned from you some years ago is the word rusticles. so what is a rusticle and why are they so interesting?

Rusticle is a term that was first coined with Titanic and it basically is what it sounds like: it's a rusty-icicle structure. Sort of stalactite-type structures and they're created through the microbial degradation of wrecks. They're found globally, as far as we know. It's basically just a term that easily describes a visual of what it is. They're made up of the bacteria who mine the iron and the manganese and all these elements out of the steel and aluminium, and create these homes for themselves, if you will. But they're so much more than that, it's a beautiful structure inside. They're extremely detailed inside this rusticle, this outer casing, and there's all sorts of tunnels and crevices and everything for water flow and gas exchange and nutrient uptake.

I always thought they make it look like the wreck’s melting. it looks like a wax model that's been too close to the heater.

It does almost look like it's melting but the process to build these structures over time is extremely detailed. They're just a beautiful example of how bacterial life on some of the deepest wrecks in the world really become the dominant organism down there. They're not solid, their structures are extremely complex as well as fragile. But for the environment that they're in, they're quite sturdy.

so, from a biological point of view, we can learn a great deal from shipwrecks because they provide a hard substrate that perhaps might not have been there before. but what can we learn from exploring deep wrecks from an engineering perspective?

Well, all engineers are taught that corrosion is a chemical process that breaks down steel and the sea water really accelerates the corrosion aspect. But from a biological perspective, we’re looking into how the bacteria found in these steel wrecks are very good at manipulating charges. We've just started the long-term examination of how these manipulative charges aid biological growth because bacteria are capable of manipulating these charges for their own benefit, meaning easier or more quickly are they able to degrade these steel shipwrecks. So as far as engineering goes, these bacteria are influencing the speed of the collapse and degradation, so they've done a very good job of degrading the ship faster than expected. So that leads to collapse of things like decks or masts or outer shells. And they seem to be doing it both inside the wrecks and outside the wreck.

so from the point in which the titanic landed on the bottom, other than the rusticles, has it actually changed much or is it still largely what it would look like 100 years ago?

Hull of Titanic (image courtesy of Richie Kohler)

No, the wreck of Titanic has changed considerably since the sinking. Obviously, we only have a picture from when it was first discovered to present, but decks have collapsed. Plus, we have been able to predict, through examination of the biological degradation, the collapse rate to a certain extent. But because it's happening from both the inside and the outside, it's very difficult to gauge how quickly it's going to collapse simply because we don't have a good understanding of the rate of degradation from the inside. We can visually see and test on the outside but very few experiments have been able to penetrate the wreck and get a firm understanding of that degradation. But if you look at the bow section of Titanic, the back where the sections broke apart the decks have collapsed in on themselves and will continue to do so.

so if I were to guess the year that the titanic will collapse, how many years time is that?

It depends what it is that is collapsed. So when all the decks have collapsed, that would be probably within the next 50 to 75 years. There's really nothing there that can out-compete the biological degradation, so it will end up being just sort of a u-shaped structure on the sea floor with the decks collapsed in on itself.

and how long is that wreck going to be affecting the surrounding area for? surely a big hunk of Steel is going to be there for hundreds of years right?

Oh definitely. It will eventually go back to nature, which is just an iron blob on the floor, but because it's created such a habitat for such a diverse range of deep sea life it's going to be hundreds if not a thousand years for degradation. It won't look look like Titanic, but yeah it'll be around for a while.

can you tell us a bit more about Bismarck?

So Bismarck is extremely deep, so it takes a while to get down there. Over three hours to get down to the bottom. But it's very much looks like a warship, you can see the swastikas on the deck, you can see torpedo marks on it. It's very dark. The rusticle growth on the outer shell is actually quite minimal. The bottom section is missing from the shipwreck itself, and in that, it’s just streaming with rusticles. One of the most interesting things from Bismarck is they had a number of planes on board and they had a lot of aluminium structures to those planes. On those is where we discovered the elusive white rusticle.

like the white whale!

Rusticles on the Bismark (Image courtesy of Droycon Bioconcepts Inc.)

Exactly. And that is from the aluminium being mined by the bacteria. So it creates these white rusticles and we have since seen them on other wrecks with a large amount of aluminum on them. The structure is obviously younger than Titanic, as far as when it's sunk. But whatever the steel making process that they used when they built the outer sheets for Bismarck was very good at being biologically inhibited for the bacteria.

yeah presumably because the ships are painted in anti-fouling paint, that must surely slow things down a bit?

It does on that surface alone, but once a wreck is submerged in salt water, they will attack the steel from the other side. So, if you looked at something that has anti-fouling paint, on the other side of it the bacteria are continuously attacking that specific area. And what they do is they take everything that they need and they will leave almost a carbon skeleton of what the steel is. So, unless there's weight on it to crush it, that carbon skeleton will remain intact and it look’s like: ‘oh well there's no biological activity or corrosion occurring here’ from one side, but the other side is basically just carbon.

wow that's amazing! do you have any idea (with the the wreck being the center point) how far horizontally is it having an effect? I mean all the stuff getting buried into the sediment surrounding it. if you have to take a core sample from 50 meters, 100 meters etc, how far away can you still pick up signatures from the wreck?

Oh yes, I think that the furthest they've got was five to seven kilometers away. Yeah it's it's a huge area that is being inhabited - it's creating its own little microbiome in there and just living quite happily off of the feast of elements from the steel and everything else that Titanic had in it. It really brings together the idea that nature really does rule all and no matter what environment it is, what we think is a harsh environment, it it's just teeming with life.

are there any other interesting facts about these big wrecks you want to share with us?

There's so much work that that still needs to be done, we have put long-term experiments on a number of wrecks and these determine the rates of growth and types of growth and that sort of thing but I'd really like to try to meld some genetics in there; some more multifaceted expeditions. A lot of play goes to engineers and marine naval architects and historians and things like that, but I really think that the science is key to understanding how our oceans and our ocean communities, particularly the deep ocean, all work together to make the environment that they're in. It's very difficult to convey to people the importance of the biological nature of degradation, and not only for the wrecks, the wrecks are are just a point in which people can to visualise the bacteria in the ocean, but they're everywhere. How are they affecting the health of these oceans over the long term?

it feels like the wreck is just pulling the bacteria out of the dark and into the light, if it wasn't there you could drive around you wouldn't really appreciate the intense microbial action that's going on, until you put a wreck in it and over long periods of time just watch it dissolve. there's something really beautiful about that, it's very poignant.

Right? This is what the power of these microbes really have in the overall impact in society. There's corrosion everywhere and how much of it is biological? How much of it is chemical? Or is it actually a combination of the two? I guess one thing I'd like to clarify is that when I say biological or microbial degradation, this isn't one type of bacteria with all these wonderfully latin names. This is a consortia, huge groups of bacteria that work together. So you have this vast array of microbes working together to survive, not only at these extreme depths with no sunlight but with resources that when you plop a shipwreck down there, they become abundant and they take over.

Image courtesy of NOAA

it's almost like nature is just undoing your mistakes. it's like: this isn't supposed to be here and there's all these little critters just making it go away. it might take a thousand years, but they'll get there,and then it’ll just be an orange smudge on the bottom of the ocean.

Yeah, nature is very good at removing or at least using what they find there to survive, but eventually to break it down into the iron ore that made Titanic in the first place.

what's your thoughts on preserving the historical significance of these things? thinking of wrecks as a collection of artefacts? I've heard both sides of this and I'm just curious to know what how you would feel about that?

That's a tricky question. I am of the mind that it's a very human thing to want to collect things. Whereas, I have approached and will always approach wrecks for the majority of the time as graveyards. They are to be respected, they are not necessarily to touch or take from. I think there's so much more to learn other than artefacts or trying to save pieces and wrecks. I guess if it's off the wreck and it's sort of in a debris field, bring them up take them, whatever. But we have a huge history of the physical entities of Titanic. How it was made, what was in it, we know people who are aboard, we have personal items. But it's really a site that I don't think should be touched.

The wreck itself should stay as it is and we should look past the physical things like artefacts and more into the beauty of the environment itself, the degradation in itself. It's probably not the popular opinion but there's no scientific value, there's no real historic value other than selling tickets to people.

yeah you're right. ultimately, it comes down to: someone's going to make a lot of money from bringing that up.

I always have to depend on documentaries to go and investigate these wrecks from a scientific standpoint, so it’s not a popular opinion when you say: ‘oh, don't take that. Don't touch that.’ Right? I run on the strictly non-invasive side of things, so it's probably not a popular opinion.

well to be honest, I agree with you. I think it's more interesting to see how it eventually dissolves and how it sort of slumps back into its original natural form rather than seeing it in a museum in Las Vegas or something like that

well that's all the questions I've got for you lori, I just want to say thank you very much for coming on the deep-sea podcast!

I appreciate this, thank you very much.