We speak with Teresa Amaro about the turbulent world of submarine canyons

Listen to the full interview on The Deep-Sea Podcast

want to be notified when new interviews are released?

Teresa Amaro

Marine ecologist at the University of Alveiro

I'm joined by Teresa Amaro, a deep sea ecologist currently based at the University of Alveiro. Her research interests cover trophic ecology of different deep sea ecosystems, and that includes and what we're going to focus on today is submarine canyons. Thanks for coming to have a chat with us!

Thank you for inviting me.

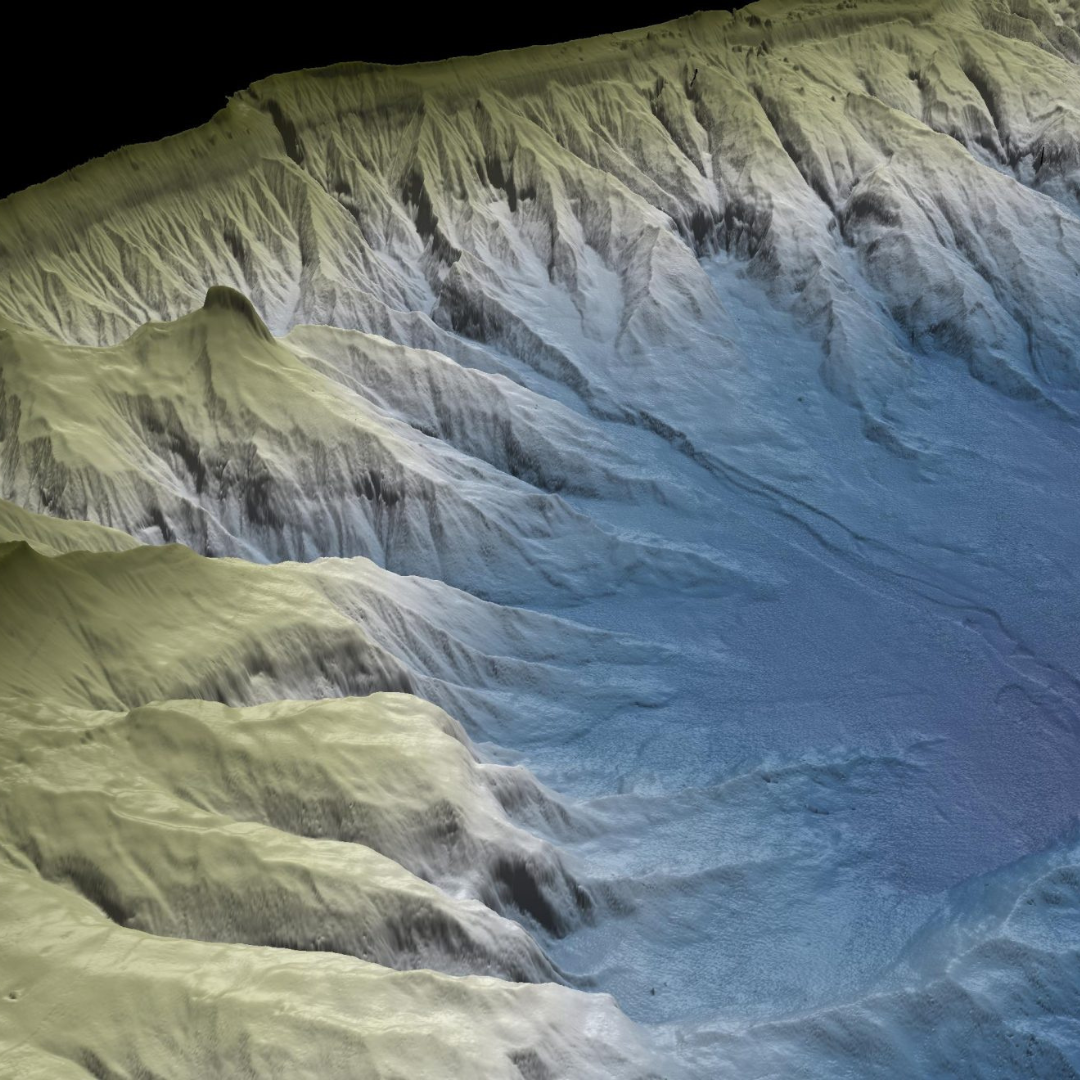

So I wanted to start by putting canyons into context. So we have the continental slope where the land transitions into the abyssal plain. But what specifically is a canyon? What sets it apart from the more regular slope?

Whenever I talk to people, I normally tell them to visualise the Grand Canyon in the US and then put that image under water. And I think it's a very good description of what a canyon might look like.

Yeah, it's an easily accessible one.

Yeah.

Do they tend to be associated with rivers?

Yes. Although one of my favourite canyons, the Nazaré Canyon is not. So, in Portugal, for instance, we have the Lisbon Canyon and the Setúbal Canyon. And they are associated with rivers. But the Nazaré Canyon, which is a little bit north of Lisbon, is not. So you can have both type of canyons.

are the river based ones the most common type?

I think so yes, because as you can imagine, you have a very big influence from the river and the currents. And then, with time, this can be transformed into a canyon. But for instance, you have the Whittard Canyon that is not associated with any land or river, it's in the middle of the ocean.

Sometimes a canyon take some kilometres to actually really start to become a canyon. But you have some canyons like the Nazaré Canyon that starts immediately at zero metres depth. So if you see it from land you see a huge cliff, and then it starts immediately from 0 to 6000 metres depth.

Wow. And that must really give different properties because if they're created by a river, there's lots of material coming in from the land. And then it sounds like there's another type of canyons that used to be formed from rivers or maybe formed just as clefts in the Earth's crust. they must have really different properties.

Yes. But for instance with the Nazaré Canyon, you do have some deposition of organic matter. And if you studied the canyon walls and the terrain, the material is really rich with the terrestrial inputs (despite not being associated with a river). So it's absolutely right what you say. But in the Nazaré Canyon, you do also find high levels of minerals. And I think I can’t really compare (for instance) between the Nazaré Canyon and the Lisbon Canyon which has river input. But I think that the Nazaré Canyon in terms of organic matter, is more enriched, and is fresher than the Lisbon Canyon, where you have a river. So the reason for that … I don't know. I think it has to do with the currents and with the oceanographic features that you have in there, but with the Nazaré Canyon especially, the organic material is really enriched and until very deep.

Which makes sense why it's a good place to live. Is there actually a definition of a canyon? Because, of course, the seabed is pretty varied. Is there a point where a cleft or a crack in the earth's crust becomes a canyon?

I think you can define a marine canyon as a deep, large-scale lesion that occurs on the continental shelf. And I think they can exist in ocean margins. And these landforms, serve as preferential particle transport conduits of organic material that can connect the coast with the deep sea.

Image courtesy of Schmidt Ocean Institute

So we know that the abyssal plains on the whole are a very static and low energy environment, and that's why this input will be incredibly important. So what are the ways, other than having more organic material in them, what are the ways that the canyons differ from the the open plains that surround them?

Abyssal plains, normally, are not rich in organic matter, and they are really dependent on what's happening in the shallow water, like the degradation of organic matter that falls from shallow water all the way to the abyssal plain. Whereas canyons, if you see the structure, it's like a river, right? And that helps to transport this material to the deep sea. And then that, of course, helps to feed the organisms that exist there.

And sometimes, these sediment flows that can be quite dramatic. So it's almost too much of a good thing for the animals that live there. There are these huge turbidity events which are like a mudslide down the canyons.

Exactly.

There's also some unusual currents that take place around canyons. There's flushing events where there'll be a huge movement of water mass, not just the the sediment moving down, but actually some of the strongest currents we've measured.

Yeah, I imagine like a snowball, that comes all the way down the canyon. It increases in volume, and then it just keeps moving down until it finds the flat terrain. So then these turbidity events, are actually perfect for the fauna there. Well… sometimes.

…As long as they're not too close….

Yeah, as you can imagine, if the snowball or these turbidity events are too strong they can damage all those animals that are living on the top of the sediment.

…or smother them if they're fixed.

Yeah, exactly. And then it will be very bad for them, but then it will help others afterwards.

Do they have much in common with the hadal trenches? They are another abyssal-adjacent habitat. Whilst the abyssal zone is quite static and you end up with long-lived animals that eek by on very little food, then you have this dynamic environment right next to it where there is this abundance of food, so the animals tend to have a higher generation time because every now and then there will be the catastrophic events that will wipe out a large part of the population. So they reproduce more quickly to bounce back after one of those events. Is there a similar thing there?

Yeah, exactly like that. I don't know much about trenches, but I can imagine that in the trench, whenever you have these events, it drags the food down. And then in canyons, if you imagine a river with the water and a slight inclination which keeps the material being dragged, and until it finds a flat terrain when can be deposited. You really have to imagine a river going slowly, slowly along.

Image courtesy of Schmidt ocean institute

are the species that exist in these environments that really thrive there, maybe some that are only found in canyons?

Yeah, there are a lot of endemic species. But as you know, we also do not know a lot about the deep sea, and we are still finding more and more deep sea fauna. I'd say so, yes, that there are organisms only found in trenches, but I tend to also think that because we don't know a lot about the deep sea, I'm not so sure if if we would find these fauna elsewhere.

No, definitely. We have a tendency in the deep sea community at least to have a lot of ‘biodiversity hotspots’ and a lot of endemism that really might just be: we've only got one sample. So by definition it's a hotspot and an endemic species. So, without saying that they have to live only in the canyons, what sort of animals do you find there in abundance?

So, sea cucumbers in those areas actually live great in the canyon. They are the first ones to appear whenever there is organic matter deposition events. All the areas of the abyssal plains and they are not there, and suddenly they appear.

They were hiding somewhere.

Yeah, I still don't understand where they're coming from. So if you go to a canyon where the organic material is fresh, they’re everywhere. And so I was like: Wow, why is that? And so I hypothesised that they prefer this fresh organic material. So I looked into the guts, and you could really see that these holothurians were eating fresh material, and this fresh material being degraded along the gut. But then you also see that whenever the holothurians do not have fresh material, they can also survive with very old material.

Image courtesy of NOAA

Is this a swimming species you were looking at?

So in in the Nazaré Canyon they were not, they were living under sediments. Whereas the species that I found in the Whittard Canyon were swimming. One of the questions that I really wanted to look at was actually to go to New Zealand and have a look at the Kaikōura Canyon and to see how different or how similar it is from the Nazaré Canyon. Because the same holothurian species are found in the Nazaré Canyon and in the Kaikōura, but i’ve never looked at the orgnaic material from the Kaikōura.

So, I really wanted to have the faeces intact because I had the holothurian, and I had the gut. So I just needed the faeces to have the full picture. So together with Ben Berman that worked at Tennessee, we built a poo collector, which worked really great. So I said to Ben that I really needed to have a device that would allow me to collect poo from the holothurians directly because when you collect the poo straight from the sediment, it’s been contaminated by the sediments.

So we created a collector, and then with an ROV, we put the holothurians inside the device. We let it be for 3 to 4 days, and each holothurian had a kind of funnel. And then whenever they would release the poo, it would fall into a vial. And then whenever we arrived there to collect the device, we just shut the vial so it could not be contaminated.

So part sediment trap, part music festival toilet.

Yeah, exactly. And then it was really nice because you could see that the gut was completely empty.

You knew you had it.

Yeah. My objective was perfectly fulfilled. I managed to collect the faeces and then I had the perfect connection. I had the sediments, I had the holothurian gut, and then the faeces. So I could perfectly study which kind of material these holothurians were eating and if there was a degradation of the gut.

So, as well as sediment, there's going to be rocky sides as well. What are some of the animals we find there?

So, we find filter feeders, like corals. And although I've never had the chance to study them, we have the deep sea sponges as well.

So there's multiple environments there. There's these rocky sides and then the sediment at the bottom. But it's a really complex environment. There's a lot of dynamic things going on. How do you sample there Because it’s tricky?

Image courtesy of NOAA

Yeah, it's really hard. So I think you first have to study in detail how the canyon is formed and see where you can go with your gear, either with the lander, with the sediment trap or with the ROV.

I accidentally did a transect with a lander, it was during one of these flushing events and I was measuring over 40 centimetres per second flow, and the lander was just being pushed along the seabed. usually we've got loads of ballast and they hardly move. And this was real force. it travelled a long way.

But you managed to retrieve it right?

Yeah. And then I got this amazing transect as my lander was bashed along.

What do you think Are the big questions that still lie ahead? What are the the big questions in canyon research?

I think they're still the same as always. We find out lots of things. We discover lots of new things. We discovered they are really hotspots of biodiversity, but I think the questions are still there. How come the species or the organisms survive? How come these turbidity events happen? How and why do these fauna survive?

Image courtesy of NOAA

I still want to do multidisciplinary research on canyons, because it's not good to only focus on biology. You have to do multidisciplinary research and you have to go on multidisciplinary cruises to actually understand what's going on there. I learned that with all my cruises, I was really lucky to have the geologists there. I learned a lot from the geologists, and they were always the first ones to go in. And then us biologists would go there. So I tend to say that I'm not a biologist anymore, because I try to answer my questions based on a multidisciplinary context.

yeah, so often your biological context is answered by the geologists. You know, you're wondering like, well, why is this here? Why wasn't it over there? And then they'll just chime in with: ‘well, this one's really old and that one hasn't existed long enough.’ And then, that's it. The biological answer is answered by the geology and chemistry.

Yeah, so I tend to say that now I'm a biochemistry ecologist, but I need the geologists with me all the time, I think.

Everybody does. I need a geologist.

Right?!

Thank you so much, Teresa!

Thanks for having me.